Introduction

Seligman (2011) suggested that skills that enable surviving in the face of challenging circumstances were a universally desirable ability to have. However, despite resilience being the subject of many research projects with attempts to define, operationalize and measure it, a consensus has not been found (Coutu, 2003; Meredith et al., 2011). Many researchers have pointed to the decline in mental health experienced by many following the Covid-19 pandemic as a reason to focus more attention on resilience. However, resilience is not conflated solely with positive mental health; there is also an element of positive functioning involved in the construct (Pemberton, 2015).

Historically, researchers started to study resilience when they noticed that some children did not respond to adversity with the expected negative outcome (Garmezy, 1993). Therefore, they concluded that there was an innate quality in these children that enabled them to be resilient or that protective factors or lack of risk factors enabled them to recover their positive life trajectory (Hauser et al., 2006; Wagnild & Young, 1993). Later research showed that recovery is the norm rather than the exception (Masten, 2001), and that in addition to the protective factors, individuals adapt to adversity through a series of processes. These processes can be cognitive, emotional or behavioural mechanisms that lead to the positive outcome observed by the earlier researchers (Lines et al., 2020). This means that resilience is a multifaceted construct that has a number of stages which lead to different outcome speeds.

The diagram shows the current understanding of resilience as being required following adversity and involving both protective factors and processes that lead to four different outcome speeds (Carver, 1998). These speeds are resistance, quick bounce-back recovery, slower recovery and reconfiguration, known as post-traumatic growth (Ivtzan et al., 2016). Looking at the processes of cognitive, emotional and behavioural adaptation, it becomes clear that resilience is something that can be enhanced by using tools and techniques that support cognitive, emotional and behavioural functioning, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (Beck, 1988). This finding has led to the creation of intervention programs designed to teach these skills, such as the Penn resilience program (Gillham et al., 2007) and the SPARK resilience program (Boniwell et al., 2023). Both of these programmes started by targeting the resilience of young people in education and have then been developed to include broader populations.

The advent of Positive Psychology (M. E. Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) brought with it the idea that people could move from languishing into flourishing by using interventions designed to support wellbeing. This would provide a buffer from ill-being following adversity, as a person would be flourishing before the adversity struck and have tools and techniques to support themselves through the challenge. While flourishing is a state that is highly desirable to experience, the idea that this place can be attained through learning creates the idea that happiness has a privileged position as a superior emotion. Additionally, it suggests that the best route through adversity is to remain happy, which creates additional pressure for someone already facing challenging circumstances (Held, 2004). This message also discounts the impact of the environment on the individual and the responsibility of those who have the power to create that environment and to consider the wellbeing of those within it (Bronfenbrenner, 1981). This would suggest that any model of resilience should not focus purely on the individual as being solely responsible for their resilience. It would also suggest that resilience would be best supported in a more bespoke fashion rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. This makes a coach or therapist best suited to the task, as they deal either one-on-one or in small groups of people. A Positive Psychology Coach is ideally placed to support someone who wants to explore their resilience due to the dual focus of Positive Psychology Coaching on performance and wellbeing (Van Nieuwerburgh, 2014). A Positive Psychology Coach can also provide support for a person going through different types of adversity, as interventions that have previously worked might not work under new circumstances (Pemberton, 2015). The practical approach taken by a Positive Psychology Coach also utilizes the idea that resilience is something to do rather than something to be (Bishop, 2025). To achieve this support, though, it is important to have clarity on what people do to recover from adversity. Lyubomirsky (2014) suggested that there was a goodness of fit in selecting Positive Psychology Interventions; however, at present, resilience training programs tend to take a more one-size-fits-all approach using predominantly cognitive approaches (Boniwell et al., 2023; Gillham et al., 2007). These programs are undoubtedly successful at helping people to be more resilient, as numerous research projects have supported their efficacy (Gholami & Vahedi (2016.; Bastounis et al., 2016; Green et al., 2022); however, a research project has not yet explored this question.

This study has focused on one group of people facing a similar life challenge, that of parenting a child with autism. Research has shown that 20% of parents of children with autism suffer from Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (Baylot Casey et al., 2012). Another study found that 79% of mothers of children with autism were significantly depressed following their child’s diagnosis (Lounds Taylor & Warren, 2012). One of the reasons for this is that they might feel they are suffering from ‘chronic sorrow’ (Olshansky, 1962) as they deal with a ‘living loss’ of the expected child (Roos, 2018) with events such as school graduation, birthday party invites and weddings etc. being cast into doubt. Due to the complex nature of autism, parents are faced with the confusing challenge of working out which expected events in the future are lost, leading to higher levels of chronic sorrow compared to parents of children with different disabilities (Batchelor & Duke, 2019) Parents who receive a diagnosis of autism are also given a very poor prognosis about the skills that their child might never acquire like speaking meaningful language, have friends, be able to get a job, be toilet trained (Kaufman, 2014; Ratcliffe, 2013).

An additional challenge of parenting a child with autism is that there is considered to be a critical window when the child is young in which a child develops, which adds pressure on the parent to become a therapist during the child’s early years (Fletcher-Watson & Happé, 2019). There are also very few funded therapies that are provided, leaving parents to search in their own time and at their own expense for possible solutions to their child’s symptoms (Wetherston et al., 2017).

The most challenging aspect of raising a child with autism is dealing with their behaviour (Allik et al., 2006). This can include property damage, injury to self and others, complex rituals that disrupt daily life, tantrums and meltdowns (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; Bouma & Schweitzer, 1990; Lee et al., 2008) and a lack of social interaction skills (Ludlow et al., 2011). Another factor affecting the challenge of parenting is the level of functional language that the child has, with lower levels of language ability being positively related to higher levels of distress in the parents (Ello & Donovan, 2005).

Despite these challenges, there is research that demonstrates these mothers show resilience (Beighton & Wills, 2017; García-Lopez et al., 2016). Some studies even suggest that having some stress in life can have a toughening effect, provided that it isn’t too severe and that there is sufficient recovery time (Başoğlu et al., 1997; Dienstbier, 1989).

These challenges demonstrate that mothers who have autistic children would make a useful group to study to elicit a detailed model of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that create resilience for them. Using a group of people as a quasi-case study (Sarantakos, 2005) would follow in the footsteps of the early resilience researchers who looked at children living in poverty as a way to understand resilience (Garmezy, 1991).

This project is part of a larger study by the same author (Bishop, 2025) and so uses the author’s own resilience cycle model (see Part 1, 2025) as the basis to present the findings in this research. It is a qualitative study using a constructivist grounded theory method (Charmaz, 2014).

The wider project focused on these research questions, with this particular article focussing on the findings from the overarching question and the third question in the hope of uncovering the way that mothers of autistic children do resilience:

Overarching question:

To what extent do mothers of children with autism experience resilience, given the challenges and stigmas of parenting their child?

Then there are three sub-questions:

-

What does the word resilience mean to mothers who have children with autism?

-

How does being a parent of a child with autism affect the mother’s resilience?

-

In what ways do mothers of children with autism demonstrate resilience?

It is hoped that this study will be of interest to individuals seeking to understand their own resilience as well as helping professionals such as coaches who want to support people dealing with life’s challenges. It may also be of interest to the broader field of positive psychology as it creates a synergy with other theories within that field.

Methodology

This study utilizes a qualitative methodology due to the very nuanced nature of the research questions. A constructivist grounded theory method by Charmaz (2014) was chosen as it was hoped that a new model of resilience would emerge. A quantitative or mixed methods approach was considered early in the planning process but rejected due to the way that quantitative scales are constructed on prechosen domains. This means that they would only measure the building blocks of resilience that the creators of the scale believed to be salient to the construct of resilience. Creating a new resilience model required a more inductive approach that would allow something different to emerge.

Design

Charmaz’s (2014) constructivist grounded theory was chosen for its potential for theory creation. Finding a more nuanced model of resilience requires a deep understanding of individual experiences, the way that they construct their experiences, and the meanings that they apply to them. What was needed to answer the research questions went beyond a description of the participant’s thoughts and feelings to include their behaviours. Charmaz’s (2014) constructivist grounded theory includes a study of what the participants are doing. This provided insight into each person’s behaviours so that similarities and differences could be observed.

Semi-structured interviews were chosen to allow the participants plenty of freedom to tell their stories and take the interview in any direction they chose. This is important because it enables the conversation to move outside the researcher’s experience (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2018). An interview schedule was used to ensure the research aims were included in the discussion.

Participants and Recruitment

The chosen cohort for the participants was mothers who have children with autism. This group was chosen based on the research that suggested that mothers of autistic children experienced chronic moderate to high levels of stress as a result of parenting their children (Eisenhower et al., 2005). Having a group of people all facing a similar challenge means that they operate like a quasi-case study (Sarantakos, 2005), enabling the phenomenon of resilience in a challenging environment to be studied in a real-world environment (Robson, 2002). Fathers of autistic children were excluded from this study to maintain the highest level of homogeneity possible.

Therefore, The participants were recruited using purposive sampling to enable only those who could contribute to the topic to participate. As mothers of autistic children often know other mothers of children with autism, it was expected that some snowball sampling would occur (Coolican, 2009).

The participant selection criteria were:

-

Mother of a child with a formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

-

The diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder should have been given five or more years ago.

-

The mother should be at least 18 years of age.

-

The child should be living in the same house as the mother.

-

The family should be resident in the UK (unless an online interview is arranged).

Recruitment began once ethical approval had been granted. It was expected that the majority of participants would be recruited from autism community pages on social media. So, the gatekeepers of these community pages were approached, and permission was obtained to post an advertisement in the group. Due to the nature of data collection in grounded theory, participants were recruited in small groups.

Seventeen participants were recruited throughout the study, ranging in age from 25 – 62 years of age. Some mothers were married, some were single, some were divorced, and some were in non-cohabiting relationships. Some had one child with autism, some had two and one mother had three autistic children. The majority of mothers were white British in nationality, but there was also one Asian participant, one American, and one mother from Bulgaria.

Data Collection and Analysis

The grounded theory data collection and analysis process is simultaneous, iterative, ongoing, interactive, and intuitive. Attempting to explain this literally would result in a long and confusing account. Therefore, it is presented as a linear process to enable clarity in presentation. For this reason, the established norms of grounded theory allow for the presentation as a single trajectory (Suddaby, 2006).

The interview began once a participant was recruited, and the relevant ethical paperwork was completed. Each participant had their own semi-structured interview, which lasted around an hour. After a short period of building rapport with the participant, the interview questions were asked informally. The aim of this was to build trust with the participant so they would share their stories. As the researcher is also a mother of a child with autism, this was disclosed to encourage the sharing of stories of the more challenging side of parenting a child with autism as the participant would feel surer of an empathic response during the interview.

The questions were designed to encourage storytelling, such as:

-

Can you describe a significant event that has occurred with your child that you felt was challenging and explain the process of your actions, thoughts and feelings from the time it happened onwards until a time when you felt OK about what had happened?

-

How do you think you have overcome the challenges of raising a child with autism?

The interviews were audio recorded so that they could be transcribed, and the participants’ names were pseudonymized to maintain confidentiality. At the end of each interview, a memo was written to allow reflexive first thoughts; these memos were then included in the materials that were analyzed. The interviews were continued a few at a time until the ‘saturation’ point was reached. This occurs when further interviews do not elicit new insights into the emerging theory or concept or when the new theory has sufficient depth (Charmaz, 2014).

The method of data analysis was informed by Charmaz’s (2014) Constructivist Grounded theory method. The first round of coding, known as initial coding, involved applying gerunds (words ending in,“ing”) to each line of the transcript. This enables the actions of the participants to become the focus of the coding process. The next coding stage is focused coding, which involves taking forward the codes most relevant to the research questions. In this stage, I removed all codes that related to the thoughts, feelings or actions of everyone in the data except the participants so that only the participant’s comments about themselves remained. Each decision taken was recorded using a memo so that a paper trail of decision-making was kept. Reflective memos were also used to capture personal reactions to the analysis process.

The interviews were then compared to each other, and similarities and differences were noted as part of the axial coding stage. Once this stage was reached, an iterative review took place to ensure everything was as efficient as possible. The interview questions were reviewed to make sure that they were encouraging the most pertinent information to be shared and then the whole process repeated with the next small group of participants.

The final part of the coding process was theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2014), from which the new conceptual model of resilience emerged. This involved examining the way that the axial codes related to each other with the relationships or associations being labelled with a theoretical code name. These codes were then used to inform the new model of resilience. This particular project required four iterations of this process to reach the point where a model of resilience emerged. A check back interview was then arranged with one of the earlier participants using Guba and Lincoln’s model of trustworthiness (1989). This involved asking the participant to sort the subcategories under the main categories to see if their experience was congruent with the final result.

Findings

A large part of the findings from this study have been presented separately (Bishop, 2025). However, the findings presented here have been held back so that they can be given more focused attention. The research questions studied were as follows:

To what extent, do mothers of children with autism, experience resilience, given the challenges and stigmas of parenting their child?

Additionally, the three sub-questions formed the structure of the research process:

-

What does the word resilience mean to mothers that have children with autism?

-

How does being a parent of a child with autism affect the mother’s resilience?

-

In what ways do mothers of children with autism demonstrate resilience?

The main focus of this article is on the findings from the third sub-question and its relation to the overarching question. The main finding to be reported here is that something novel was observed during the axial coding stage. In comparing chunks of data from one interview with another interview, it was clear that the participants faced very similar challenges but that they moved through their challenges in ways that were different from each other but congruent with themselves. This led to the theoretical code of resilience signature. An example of this is looking at two participants who were dealing with their child who was having a ‘meltdown.’ Cara (a pseudonym) stood back and waited for her child to calm down, whereas Monica used herself as a weighted blanket to provide deep pressure for her child to help them calm down and prevent him from throwing bricks. The next part of the axial coding process involved comparing portions of data from within the same interview. What became apparent here is that each participant dealt with their situation in a way that was congruent with themselves, which was observed by viewing their narrative from several situations. An example of this is Alicia, who arranged a meeting with health professionals to resolve her challenges:

“It was all really complicated because she failed her hearing test when she was little, so we knew that she had glue ear and every time that we went to the hearing specialist at St Helen’s, it always seemed to be at a good point in her hearing, and then two weeks later she would get a cold and lose her hearing. So, we would’ve been discharged, and then we would go back to the GP, and he would say Oh her hearings terrible, so we will get you back on this waiting list, and it was this endless cycle of trying.” Alicia.

Further on in the interview, she said:

“…she got put on the SEN register for kind of concentration and focus and being able to organize her work and those kinds of issues and I was still saying ‘what is the issue what is the underlying issue?’ Do I take her to the GP do I take her to an Educational Psychologist… all of these sorts of things’. I took her to the GP once and the GP just said Oh the school would tell you if there was really a problem, go away. We took her to an Ed Psyc, and they said she has a massive range of skills she was in the top 99.8 centile for some things, and she was in the bottom 0.2 centile for other things and the Ed Psyc said that she had never seen a profile like it.” Alicia.

Alicia also created a lot of practical strategies to facilitate her child’s independence:

“I get up and have a shower, by which time four different alarm clocks have gone off in her room including one that goes light so that she is hopefully awake by the time that I knock on her door and say are you awake and I’ve had my shower and we are trying very hard because she is now 19 to not manage her out of bed and into the shower and getting dressed and everything else so we have put in place a lot of routines over the last few months which are around her being organized for herself because she is desperate not to be treated as a child.” Alicia.

Then, in another place in Alicia’s interview:

“…she is now kind of much more in control of what is going on in her own head [….] learning how to cope with the situations, I’m not needed on a minute-by-minute day by day basis in quite the same way so there are times you know where I kind of jump in and say let’s sort out your routines because that’s such a big thing for her.” Alicia.

So, it was clear that Alicia had a very practical way of dealing with her challenges.

It became apparent that all the participants moved through all the stages following adversity through recovery to adaptation in a congruent way. Bianca used cognitive strategies first to decide what to do in a crisis:

"I turned round, and T was standing on top of the wall that overlooked a squash court and there was no… it was focused, and he looked like he was about to jump. I don’t what level of time, I thought how do I get to him without alarming him so that he does jump.

The congruency with herself shows up in her choice of a highly cognitive activity to do when she has downtime.

“one of the things I have done since T’s program is script writing classes and it is in my screen play based on everything that has happened.” Bianca

While cognitive activities is the first place Bianca goes, it isn’t the only thing she does, demonstrating that her style has a hierarchy. To continue the story of the visit to the squash court

“I turned round, and T was standing on top of the wall that overlooked a squash court and there was no… it was open, and he looked like he was about to jump. I don’t what level of time I thought how do I get to him without alarming him so that he doesn’t jump. So, I just ran fast as silently as I could fast but gently no sound from him. I put my hand in front of him so that he couldn’t 't fall and just took him down and sort of held him. My heart was beating so fast I was just so relieved that I had got him.” Bianca

From this excerpt, it is clear that thought came first, followed by physical action, and then, some time later, emotional reflection.

Another example of this hierarchy is Petra’s story:

"So, one was in my little girls assembly, when [I] had taken B with me, and he was screaming and running around and then he used to try and pull his trousers down. Which again I just got up and walked out with him and thought I just can’t stay with this and couldn’t cope with this. He still does it a bit now. So, I just walked out with him and then cried when I got home sort of like, I can’t do this anymore, why have I got to have a child like this? So, of you know, that sort of thing, and then I think really my husband is really good with that reassurance, you know this is how he is, and that there is help out there. I sort of just have a bit of me time and then I feel alright.

Her first response is physical as she removes her son from the assembly. She does not have an emotional response until she gets home. Some social support from her husband then helps her to feel better, followed by some time out from parenting, which in another place in the interview, she describes the physical activity of having a bath for this purpose. Therefore, Petra would have a physical response first, then emotional, and then social support as her recovery plan.

The memo that was written following this observation was:

“In comparing the interviews with each other, it is apparent that the participants are different to each other but that they have a congruency with themselves. Alicia is really task orientated, whereas India relies on her social skills. Bianca is very dominant on cognitive reframes and activity whereas Fiona has a strong faith which both is a source of comfort and structure to her life. I find it odd that I am surprised by this discovery as surely it is a well-known fact that people are different to each other, but that personality traits are enduring!”

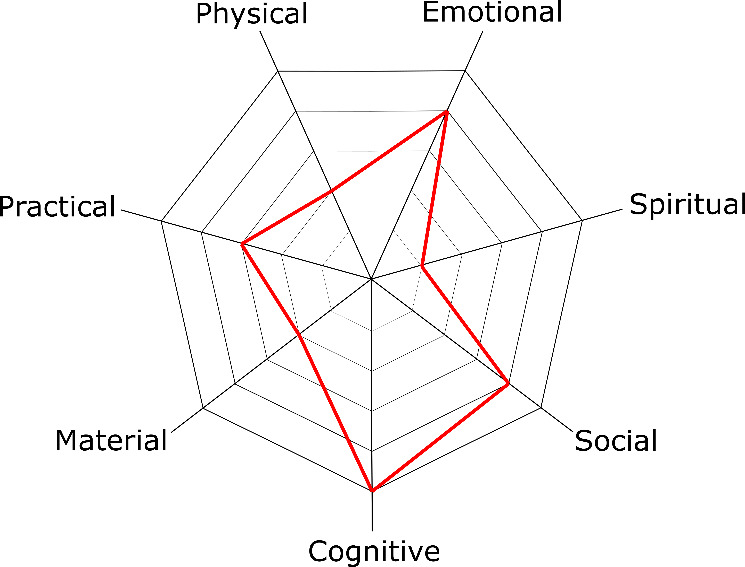

This observation made the last theoretical code of resilience signature to cover the unique way that each participant dealt with the very similar situations that mothering a child with autism brought. On return to the data, it emerged that there were seven categories of response: Cognitive, Practical, Social, Physical, Financial, Spiritual, and Emotional. Each of the participants used several of them in a hierarchical fashion that was personal to them.

This table shows examples of the codes that fit under each category:

The following table shows how each of the strategies was used by each participant with the number of times it occurred in their interview being listed.

It can be seen from this table that no two participants had the same pattern of responding to the challenges of mothering a child with autism. Therefore, any model of resilience needs to take these bespoke styles of resilience of these mothers into account.

Discussion

This study was part of a larger study with the findings presented in another article (see Part 1, Bishop, 2025). The conclusions of that study will be briefly presented here to give context to the discussion on the theoretical code of resilience signature.

The study resulted in a conceptual model of resilience that was presented like this:

The conceptual model of resilience presented in that study was based on the finding that resilience occurred in discreet sequential stages. The model begins with the adversity, which must be managed in the stage of adversity management. Then once the adversity is managed, there is the adversity aftermath, where the participant reactions happen. From here on, the next stage is a period of recovery that might involve resting. Once the participants were feeling better, the adaptation occurred. However, the novel part was that the reason for the adaptation was not just based on the adverse event, but there was a degree to which the adaptation happened so that the adverse event could not happen again. All of these stages occurred within the context of the environment, which was shown to both impact adversely and support the participants. It also was an area that was seen as possible to influence but not control (Covey, 2020).

The resilience signature to be discussed in this article completes this model by being represented by the larger grey arrows. This shows the movement of the participant around the cycle, with each movement being congruent with previous stages for each individual, and so would be represented by this diagram:

To suggest that individuals have a signature style of moving through life is not a new idea. However, it is novel to use this concept with regard to models of resilience. Seligman (2005) suggested that individuals have signature strengths they use in the face of adversity. These strengths also exist in a hierarchical way, with each person having their own pattern of strengths selected from a list of 24 strengths. By building their strengths, a person can create a buffer against adversity and assist in the speed of their recovery. It is by uncovering each person’s hierarchy of strengths that this can be facilitated. On comparing the signature strength profile with the domains within the resilience signature, it is clear that there is some overlap between the two models, with strategies like learning more about autism fitting into the practical strategy in the resilience signature and under the love of learning in the signature strengths. Zest, being a physical style, perspective, curiosity, and fairness, fits into the cognitive domain with the strengths of kindness, love, hope, and forgiveness, and it fits under the emotional style in the resilience signature. Spirituality also features in both models. Domains like financial style do not fit into the signature strengths, demonstrating that the signature strengths, though a well-validated theory, cannot be a complete substitute for this group of participants in explaining their resilience.

Another difference from the signature strengths model is the place within the resilience cycle and the signature for emotional distress. Bryant (2022) suggests that we need to allow space for emotions like feeling upset as they are a healthy part of responding to an unwanted event. Indeed, there are some events in life where it would be considered unhealthy for someone not to feel upset, for example, the end of a cherished relationship. This challenges the assumption that is so often made that ‘staying strong’ and not expressing distress equals a resilient response. Shah (2022) argues that this is an unhealthy response and may possibly, in the end, prevent or delay healthy recovery, leading to what she calls ‘dysfunctional resilience’, which feels like one step away from burnout.

Other theories within the psychological theory that support the idea of a personalized style of moving through life are models such as personality type theories. The Big 5 theory of personality (Costa & Macrae, 1992) suggests that each person exists in a unique pattern along five domains which operate as continuums. To accept this theory means that it isn’t then possible to suggest that there is a one-size-fits-all way to deal with adversity.

One of the challenges that have faced resilience research is that there has been no consensus of opinion around one definition, one conceptual model or one scale to measure it (Meredith et al., 2011). It is possible that the reason for this is that there is so much variety in the way that people respond to adversity. Science attempts to create gold standards with theories that are comprehensive in their power to explain a phenomenon, as these are held to be the best in their genre (Brodsky & Lichtenstein, 2020). However, the lack of agreement over virtually all aspects of resilience shows that these absolutes either do not exist or have not been found yet. Therefore, a more flexible model is needed that can adapt to each individual unique style of resilience. Instead of looking for a new model to replace all other models, it is about creating a Hegelian-style adaptation to the present models that could act as a flexible synthesis of the existing theories (Forster, 1993). This could then consolidate what is already known about resilience into a more user-friendly model that can be simple enough to be clearly understood yet flexible enough to allow an individual bespoke functioning within it.

Suggested Future Research

The resilience cycle and resilience signature are new conceptual models that have been created during a single research project. Future research would, in the first place, go back to the autism community and test the model to see if it can improve the wellbeing of parents of autistic children by conducting pre-test measures and then teaching the model using a workshop. Then, the parents can be given time to use the model in their lives. After this, a post-test measure can be taken to assess the efficacy of the model.

After this, further research can test the model using a group of people either from another single community again or open it to the broader population. Another possibility would be to train coaches to use the model and then use it with their clients. A qualitative study could also be conducted with those coaches to see how a more diverse group of people received it. The aim of further research would be to advance the conceptual model to the level of a theory.

Limitations of this research

This research project involved qualitative semi-structured interviews with seventeen participants, all from within the autism community. Therefore, it was a small-scale study with a group of mothers with similar life challenges. At this point, it is not known whether this model is applicable to other cohorts of participants.

The researcher also comes from within the autism community, and so while there might be advantages to being part of the studied community, there might also be disadvantages, such as the participants not sharing information that they think is already known.

Implications for Coaching Practice

The findings of this study are an exciting development for coaches, as it provides a new way to work with those who are in the midst of adversity. The concept of the resilience signature provides a way to support clients following adversity. The resilience cycle demonstrated that the most comfortable place of the cycle was after the adaptation had been achieved. It also emphasized that each stage of the cycle was important and needed to be achieved before moving on to the next stage. This is where the resilience signature comes in because if an individual knows what their resilience signature is, then they can utilize it to complete each stage of the cycle with maximum efficiency. This then can become a ‘go-to’ strategy for overcoming adversity.

The task of the coach is to help the individual uncover their resilience signature so that they can create their personal adversity recovery plan. A possible way to do this would be to use a device similar to the PERMA wheel, based on Seligman’s (2011) PERMA theory. By asking the client to reflect on at least three past adversities they have already overcome, they can look at how they achieved that. If they wrote out the story of those events, they could then use the stories to allocate a score to each domain within the resilience signature.

They might find this prompt useful to help with their reflections:

Can you describe an adverse event from your past that you have already overcome and feel at peace with. Can you write the story of what happened starting with the adverse event and then describing your thoughts feelings and behaviours from the moment the unwanted event occurred through to the moment when you felt at peace with it.

The score can then be added to this diagram to create a visual representation of their resilience signature:

The translation of the score onto the diagram requires the coachee to allocate a score out of 5 to each domain and then put a dot on each spoke of the wheel, with a 1 being the intersection of the spoke with the inner heptagon and a 5 being on the intersection of the spoke with the outer heptagon. A score of zero in this would be right in the middle. Once this is completed, the dots can be joined to visually represent the coachee’s resilience signature. Here is a fictitious example from the data given by Bianca (not completed by Bianca herself) for explanation purposes:

Once the resilience signature wheel is completed, the coach can then assist the client in creating strategies for overcoming future adversities using this knowledge. For example, if the physical domain comes out at a 5 then a discussion can follow about what physical activities the client takes part in that might assist with the recovery phase of the resilience cycle, like taking a long candlelit bath or starting a yoga practice. If a cognitive signature comes out on top, then looking at ways to reframe thoughts using Cognitive Behavioural Coaching or using mental distractions such as reading a good storybook to provide a break might come to the fore. With the social domain, identifying who the client’s circle of family and friends are who would provide a listening ear to the adversity aftermath and then seeing if the same or different people would be the go-to people for the recovery stage if what is needed is a fun night out.

Many Positive Psychology Interventions also would fit in well to these domains, such as Mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 2006), Best Possible Self (Biswas-Diener, 2010), Gratitude (Emmons, 2008), Meaning-making (Steger et al., 2006), Yoga (Ivtzan & Papantoniou, 2014), forgiveness exercises (Worthington et al., 2000) making many ways to work with the resilience signature using well researched and well-validated tools. These tools could be used in the following way: suppose someone has the physical domain as their top score with the emotional domain second with the practical third; they could use Mindfulness to sit with uncomfortable emotions without trying to change them in the adversity aftermath stage and then use Mindful activity in the recovery stage like going outside in the garden to do some gardening paying attention to the beauty of the flowers and how they are responding to the care that they are giving them, for the adaptation stage to use Mindfulness to stay present with the current issue rather than creating a ‘my child might never’ narrative. In so doing, they are giving themselves more cognitive space to find a solution.

Conclusion

Resilience has previously been studied as a single phenomenon related to adaptation following adversity, with attempts made to define exactly the building blocks for recovery. However, this approach has the potential to cause those who don’t immediately bounce back to feel that they are failing at being resilient. This study aimed to take an in-depth look at the thoughts, feelings, and behaviours of a group of mothers of autistic children to find out how they overcame the challenges of parenting their children. Using a qualitative, constructivist grounded theory approach chosen for its theory-producing potential enabled a new model of resilience to emerge. This model, named the resilience signature, provides tools to uncover the unique responding style of an individual using a hierarchy of seven domains that demonstrate their personal response to adversity. The implication of this model is that a person can be supported by a coach to uncover their resilience signature using the tools provided in this article and then create their own blueprint plan for future recovery from adversity.

Author

Dr. Alison Bishop is an educator, researcher, and practitioner in resilience, specializing in empowering individuals and organizations to thrive in the face of adversity. As a faculty member at the Institute of Positive Psychology Coaching, she trains coaches, leaders and professionals on resilience and well-being to enhance their personal and professional lives.

Dr. Bishop has presented her resilience, hope, and optimism research at industry conferences. Formerly a lecturer in Positive Psychology Coaching and research methods within the Masters of Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology (MAPPCP) program at the University of East London, Dr. Bishop now dedicates her expertise to private coaching and leading transformational workshops.

Inspired by the courage of individuals who confront challenges and create meaningful change, Dr. Bishop exemplifies the transformative power of positive psychology in her own life, leaving a profound and lasting impact on those she serves.

.png)

.jpeg)

.png)

.jpeg)