Introduction

In their seminal introduction, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000) introduced Positive Psychology (PP) as a “science and profession which aims to understand and build upon the factors that enable individuals, communities, and societies to flourish.” Positive Psychology Coaching (PPC) is an evidence-based practice that facilitates such a pursuit. Coaches support their clients in achieving personal and professional growth, optimal functioning, enhanced well-being, and actualizing their full potential (van Zyl et al., 2020). The aim is to foster a holistic approach towards personal development, which spans across all domains of the client’s life (Frisch, 2013).

For a PPC to effectively support their client across all life domains, it is essential to understand which life domains are most highly valued. Quality of Life (QoL) is a multidimensional conceptualization of an individual’s well-being, comprised of a combined evaluation of several Quality of Life Domains (QoLDs) (Barcaccia et al., 2013; Cummins, 2005; Kuyken et al., 1995). Despite decades of research (Andrews & Withey, 1976; Diener, 1984; Diener et al., 1999; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), researchers have yet to agree upon a set of QoLDs that, in tandem, constitute QoL (Kelley-Gillespie, 2009). Furthermore, while several theories of well-being have been published (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Franklin, 2019; Maslow, 1943; Ryff, 1989; Seligman, 2011), none have provided a comprehensive list of indicators necessary for flourishing in life. Little attention has also been drawn to the overlapping nature of the theories of well-being and QoL. Nussbaum (1993) argues that well-being is synonymous with QoL, a view supported by Makai et al. (2014) who claim that “Well-Being = QoL”.

A popular tool among coaches aiming to evaluate a client’s QoL is the Wheel of Life (WoL). In her paper, Bryne (2005) explains that a client should decide which are the eight top priorities in their life at the moment. These may include: work, home life, relationships, children, finances, health, holidays, spiritual development, studying, or anything you dream of doing but have not yet got around to. However, this process of determining QoLDs fails to uphold the integrity of an evidence-based approach, which PPC aims to offer (van Zyl et al., 2020).

An Overview of Quality of Life

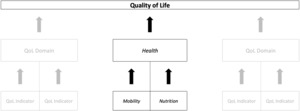

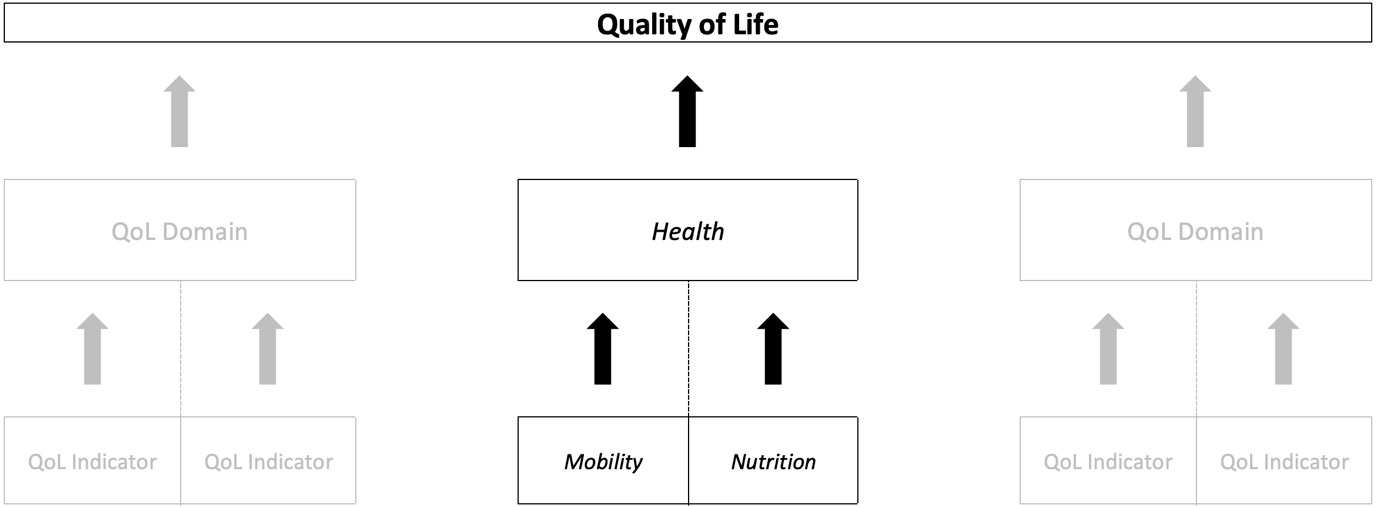

The term Quality of Life emerged during the 1960s, as social indicators of well-being were identified as a way to measure evolving living conditions (Andrews & Withey, 1976). QoL is an umbrella term containing several key features related to the psychological literature on well-being. The concept can be deconstructed from a global indicator to; QoLDs and Quality of Life Indicators (QoLIs) (Cummins, 2005; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002).

As the first level of deconstruction of QoL, QoLDs are a series of superordinate domains which categorize and encompass numerous QoLIs (Cummins, 2005). QoLIs are the second level of deconstruction of QoL and can be understood as domain-specific; objects, events, systems, perceptions, behaviours, or conditions that give an indication of one’s well-being based upon their presence or absence (Brown et al., 2013; Schalock, 2004). The greater the likelihood that an indicator has common relevance, the more likely it is to feature in a higher position in this hierarchy. For example, QoL may be characterized as life as a whole, a QoLD could be health, and a QoLI could be mobility (see Figure 1.0). Cummins (2005) suggests that a conceptual model for QoL should reflect this hierarchical structure because combining indicator variables from different levels of the hierarchy does not make conceptual or psychometric sense. The relationships between each level of the hierarchy can be compared to a nesting doll, where each component fits within its superior. Taking such an approach to conceptualizing QoL draws parallels to Ferrans’ (1990) hierarchical relationship model and fulfills the requirement posited by Cummins (2005).

The Handbook on Quality of Life

Lindström (1994) proposed a strategy of first identifying the QoLDs that define QoL, before identifying the most significant QoLIs within them. While this approach has become the most prevalent in QoL research, researchers have struggled to agree on a unified set of domains, establish consistent terminology, or measure their fulfillment effectively (Franks, 1996). As Bond (1999) explained, “there is little agreement about what constitutes the individual domains of quality of life; about the standard for each domain that would reflect a low or high quality of life; or who determines the relevance of each domain to the individual”.

The Handbook on QoL is the most extensive study on QoL to date and serves as the foundation for the present study. Schalock and Verdugo (2002) conducted a literature review on the conceptualization, measurement, and application of QoL between 1985 and 1999. They identified 125 QoL indicators and recognized that 74.4% of them could be categorized into one of eight core domains: interpersonal relationships, social inclusion, personal development, physical well-being, self-determination, material well-being, emotional well-being, and rights. This research laid the foundations for their conceptual model of QoL (Schalock et al., 2016), which has since become the most cited QoL model in the field of intellectual disabilities (Amor et al., 2023). Schalock & Verdugo (2002) highlight that the QoLDs and QoLIs identified are reflective of the dates within their study and are subject to change in the future. This study aims to investigate this change and provide a contemporary conceptualization of QoL.

A Systemic Approach to Quality of Life

Schalock and Verdugo (2002) also explained that QoL can be conceptualized within the context of the individual (microsystem), organization (mesosystem), or society (macrosystem), with each level requiring exclusive needs (Schalock et al., 2016). These needs are interconnected in nature, and fulfillment across each level results in an enhancement of QoL (Verdugo & Schalock, 2009). This paper primarily focuses on the microsystem, which encompasses the individual and the immediate social environments that directly influence their QoL (Schalock & Verdugo, 2002). However, consideration will also be given to how enhancing an individual’s satisfaction across multiple QoLDs influences both the mesosystem and the macrosystem.

QoL Domains

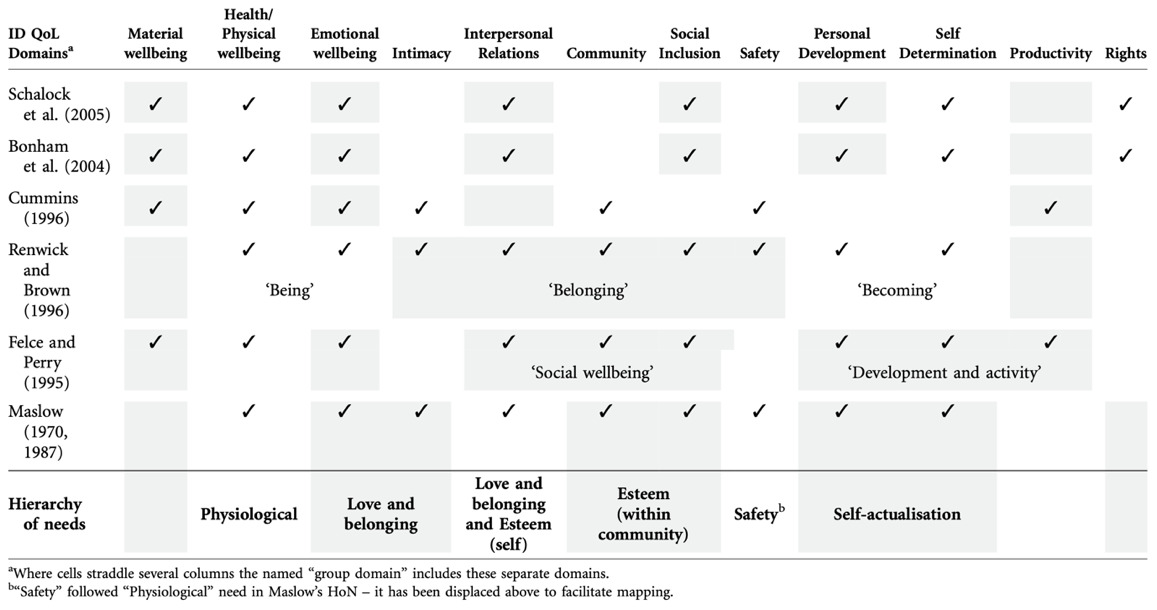

Alborz (2017) explains how QoLDs can be viewed as the needs presented in Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow (1943) proposed a series of psychological needs that he claimed would produce a heightened sense of well-being once they were satisfied. Whilst Maslow did not attribute his work to the QoL literature, Alborz (2017) argues that fulfillment of these needs would evidently improve one’s QoL. She mapped the QoLDs presented by Schalock and Verdugo (2002) and others over Maslow’s HoN, positioning each as a QoLD (Figure 2.0).

Schalock and Verdugo (2002) also presented a hierarchy in their publication (Figure 3.0), highlighting further synergies to Maslow’s HoN, whilst further comparisons have been drawn in academic and political research (Brauer & Dymitrow, 2014; Diener, 1995; Kravetz, 2014).

Franklin (2019) adopted a similar approach to mapping Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. However, he examined several key theories of well-being and drew parallels between their identified needs to present Thrive and Survive Theory (TST). By extending Franklin’s (2019) approach, the researcher proposes that fusing; PERMA (+4) (Donaldson et al., 2022; Seligman, 2011), Psychological Well-being Scale (Ryff, 1989), Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1943), Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) and Thrive and Survive Theory (Franklin, 2019) offers both theoretical and empirical validation for a potential set of QoLDs.

Furthermore, in an unpublished critique of his Hierarchy of Needs, Maslow (1966) wrote, “It must be stated that self-actualization is not enough. Personal salvation and what is good for the person alone cannot be really understood in isolation… The good of other people must be invoked, as well as the good for oneself”. As Maslow explains, self-actualization is a transitional goal that facilitates the transcendence of the ego. One must become all that they can be, in order to serve others as best as they can. Such a philosophy enhances the QoL for the individual (microsystem), organization (mesosystem), and society (macrosystem) (Schalock et al., 2016).

Figure 4.0 builds on Franklin’s (2019) work by integrating the QoLDs introduced by Schalock and Verdugo (2002) and incorporating the chakra system. The chakra system is believed to have originated in India around 1000 years ago and has since served Hindu and Buddhist yoga traditions (Feuerstein, 2001). It was first introduced to the West in the 1880s before psychologists developed a Western translation during the Human Potential Movement (Leland, 2016). In an attempt to bridge Western psychology and Eastern philosophy, Judith (2004) presents a synthesis of psychological literature and the chakra system. She explains how psychology and spirituality are integrated at their core and dissects each chakra to unveil the underpinning psychological concepts. Whilst the field of psychology is still largely unaware of the influence of the chakra system on psychological well-being, Judith’s (2004) findings show a strong correlation with the QoLDs presented in Figure 4.0 and have been included to add a further layer of depth to the study.

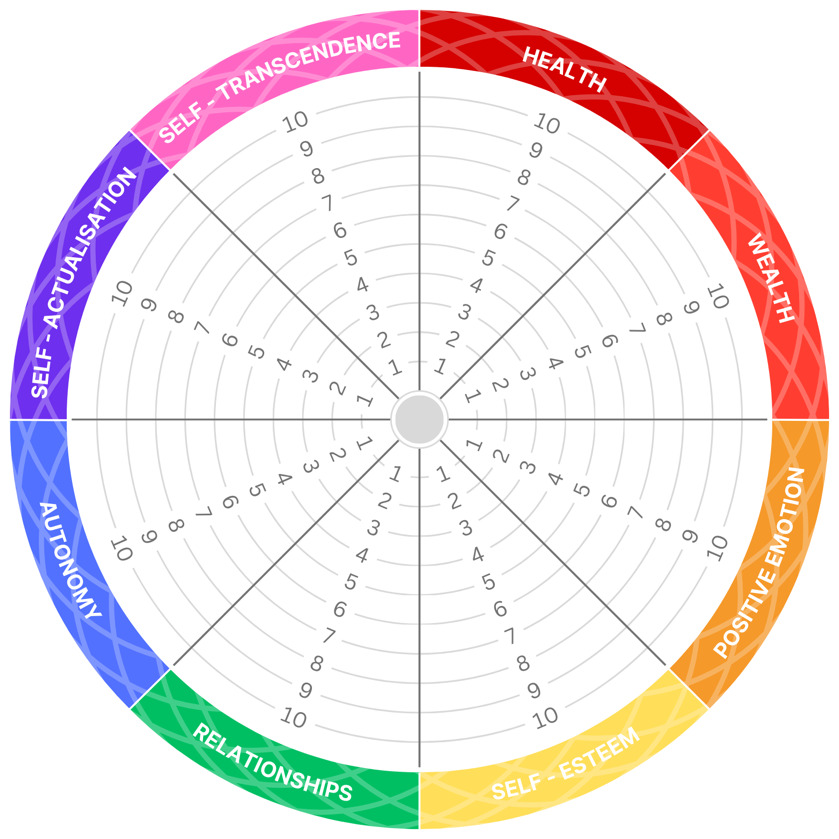

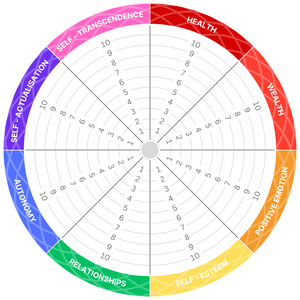

By cross-referencing these theories, eight core domains have been identified; Health, Wealth, Positive Emotion, Self-Esteem, Positive Relationships, Autonomy, Self-Actualisation and Self-Transcendence. These core domains are grouped as; Survive, Thrive and Actualise, to highlight the progressive nature to enhancing QoL (Franklin, 2019). Whilst it is argued that the research presented in this section of the paper justifies these QoLDs, further validity will be sought through a systematic review of the QoL literature.

Evaluation and Measurement

Schalock et al. (2016) argue that, in addition to a conceptual model and its theoretical components, a proposed theory of QoL requires a set of criteria that can be used to evaluate its utility and effectiveness. The inclusion of such criteria allows PPCs to measure and evaluate the QoLDs and QoLIs that constitute QoL (Schalock & Verdugo, 2002), transferring academic research into the real world. A personal appraisal is a widely used method, and several scales have already been developed (Cummins et al., 1994; Frisch, 2013; Priebe et al., 1999). However, these scales are designed to measure the QoLDs and QoLIs selected by the researchers at that time. Therefore, if the present study aims to present a contemporary set of QoLDs and QoLIs, an up-to-date measurement and evaluation tool is also required.

Rationale and Objectives

The current state of the literature underscores the need for synthesis between Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) study and contemporary research to incorporate advancements and QoL developments that contribute to QoL. A synthesis of the QoL literature is required to establish a shared understanding of the construct among PPCs. Without this coherence, both research and practice risk continuing along fragmented and inconsistent paths.

A scoping search identified twenty-one conceptual models of QoL since the publication of Schalock and Verdugo (2002), each encompassing a diverse and unique set of QoLDs and QoLIs. Additionally, the terminology was highly inconsistent; for example, the domain of health was described in eleven unique ways. These findings support the observations made by previous researchers and highlight the need to establish a consensus.

This research paper has four aims:

-

Provide further validation of the eight QoLDs presented above

-

Identify the most prominent QoLIs within each

-

Produce a model of well-being which conceptualizes QoL based on these findings

-

Create a coaching tool that supports PPCs and clients in evaluating QoL

Systematic Literature Review

The objectives of this SLR were:

-

Provide further validation of the eight QoLDs presented above

-

Identify the most prominent QoLIs within each

Methodology

Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) study analyzed 2,455 publications on the conceptualization, measurement, and application of QoL. Their strategy cast a broad net over the literature in an impressive attempt to conceptualize the topic. While their methods were considered, a unique design was created to specifically identify conceptual models of QoL since this publication. Influence has also been drawn from more contemporary SLRs conducted on the topic of QoL (Haraldstad et al., 2019; Makai et al., 2014).

The methods for this SLR follow the guidelines presented in the PRIMSA 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA statement, originally published in 2010 (Moher et al., 2010), was designed to support systematic reviewers in transparently sharing their methods with the research community. The recently updated version includes advances in both SLR methodology and terminology, whilst providing a 27-item checklist to ensure the quality and integrity of the research conducted. Furthermore, Briggs’s (2007) systematic review protocol and Riva et al.'s (2012) PICOT format were also incorporated throughout the process to provide additional academic underpinning and rigour.

Eligibility Criteria

To establish the inclusion criteria, the PICOT format (Richardson et al., 1995; Riva et al., 2012) has been advocated for inclusion within this stage of PRISMA 2020 (Page et al., 2021) and was therefore employed.

Population: Studies targeting clinical and non-clinical populations were included.

Intervention: This study did not review the effect of an intervention.

Comparison: Studies with both theoretical underpinnings and empirical validation, as per Schalock & Verdugo (2002).

Outcomes: QoLDs and QoLIs listed within each study will be recorded, provided that (a) they are original to the research study or (b) if outcomes are taken from a previous study, the cited study must have been published from 2002 onwards, and (c) the model has not already been identified.

Time: As Schalock & Verdugo’s (2002) review is widely accepted as a comprehensive analysis of the literature preceding this time, articles published between 2002-2024 will be included.

Types of Studies: The SLR will include empirical studies that have been intentionally designed to identify QoLDs and QoLIs.

Types of Publication: Peer-reviewed academic journals.

Language: English.

Location: Global.

Scoping Search: All twenty-one conceptual models previously identified in the scoping search meet the eligibility criteria and have been included.

Exclusion: Studies which do not present a list of QoLDs and/or QoLIs or include outcomes or have been taken from a previous study published before 2002 were deemed ineligible. Grey literature was also excluded from this study.

Search Strategy

This search strategy was designed to identify research papers meeting the above criteria, and followed a two-step process:

-

An analysis of the twenty-one papers identified within the scoping search was conducted to identify relevant search terms from the title, abstract and keywords.

-

These keywords were entered into PsychINFO as part of an extensive literature search.

PsychINFO was searched through EBSCOHost. The database was last searched on 02/07/2024 using the search terms: “Quality of Life”, “Life Domains” and “Well-being” OR “Wellbeing” OR “Well being”.

The following filters were applied:

Limit To: Linked Full Text

Publication Date: 2002-2024

Source Types: Academic Journals

Language: English

Methodology: Empirical Study

The researcher worked independently to review the title and abstract of all 160 records through a single screening process. Next, they conducted full-text reviews on each article, to determine which to include.

Data Collection

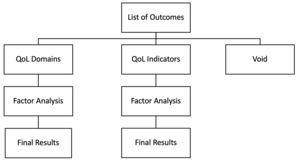

The researcher independently extracted and recorded data using a structured data extraction form. There was no need to contact any study investigators, and no automation tools were employed. All results were categorized into one of three outcome domains: Quality of Life Domains, QoL Indicators, and Void. The former two outcome domains are considered critical in this study. The classification was determined by comparing the study investigator’s definition of each outcome with the QoLDs previously proposed for the FLM. The remaining outcomes were categorized as QoLIs. Several QoLDs and QoLIs were identified as specific to the clinical population and thus deemed irrelevant to the general population. For instance, outcomes such as the time and energy of caregivers were categorized as Void. No other variables or missing/unclear information emerged during the data collection process.

Risk of Bias

The irregular nature of QoL literature presents a risk of bias across each study within the SLR and the extraction of outcomes in the present study. This arises from the subjective classification of outcomes as QoLDs and QoLIs. Additionally, excluding QoLDs and QoLIs deemed irrelevant to the general population increases the risk of bias. To minimize this risk, the researcher completed the classification through subjective analysis and presented it to an academic supervisor for verification. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Data Synthesis

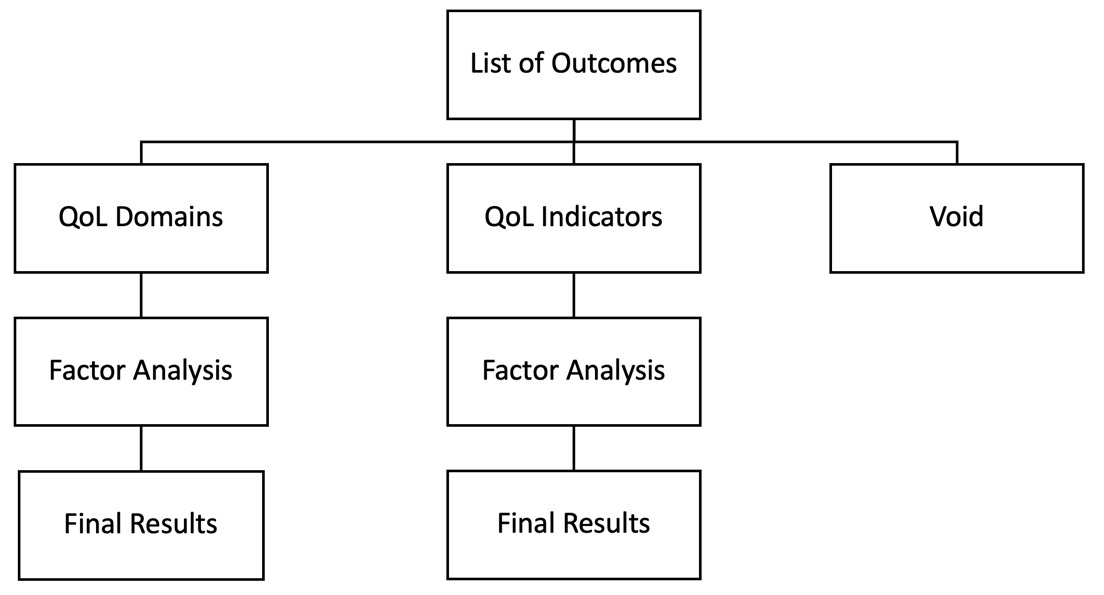

The data synthesis process parallels the methods in Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) study. The QoLDs and QoLIs proposed in each study were listed in a data extraction form, presented in the appendices to provide complete transparency to the reader (McKenzie & Brennan, 2019). After outcomes had been categorized as QoLD or QoLI, they were processed through a confirmatory factor analysis (Tavakol & Wetzel, 2020), grouping outcomes that were either duplicates or representative of comparable constructs. The purpose was to highlight their theoretical and hypothetical relationships before an all-encompassing term was given to categorize their association. These terms form the QoLDs and QoLIs presented in the FLM. Results in the QoLD and QoLIs columns were final. Results in the Void column were disregarded. This process is presented in Figure 5.0:

Definitions of each outcome were compared to assess the risk of heterogeneity. The final results are presented in a table (Figure 7.0), listing the QoLDs in column 1 alongside the corresponding QoLIs in column 2. This subgroup analysis was designed to identify and categorize the most prominent QoLDs and QoLIs in the QoL literature. Subjective conclusions were drawn by the researcher and presented to an academic supervisor for validation. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Quality Assessment

To assess the potential reporting bias, results were cross-referenced with those presented in Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) study. While there remains a risk of mis-categorization, the presentation of results is subjective and therefore finalized at the discretion of the researcher and supervisor.

Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

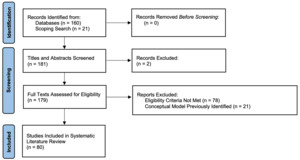

In addition to the 21 previously identified studies, 160 records were found through the database search. A total of 181 records were screened, with only two excluded due to (a) the conceptual model already being identified, and (b) a non-human study. Of the 179 full texts assessed, 78 reports were excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria. A further 21 reports that met the inclusion criteria were removed because the conceptual models within had already been identified in the present study. Data was collected from the remaining 80 studies. A visual representation of this process is presented in Figure 6.0.

Results of Individual Studies

Results from the 80 included studies are presented in the data extraction form in the appendices. As outlined in the Methods section, they have been organized into one of three outcome domains.

Results of Synthesis

The SLR provided 132 individual validations for the 8 QoLDs previously proposed for the FLM. Each QoLD was validated by multiple studies: Health (30), Wealth (19), Positive Emotion (22), Self-Esteem (11), Relationships (24), Autonomy (15), Self-Actualization (7), and Self-Transcendence (4). Additionally, 17 studies referenced a global domain, such as Quality of Life.

A further 718 individual outcomes were identified. Factor analysis produced 73 results, which were allocated to one of the eight QoLDs. Both Physical Health (30) and Mental Health (22) were most frequently cited and have therefore been presented as sub-domains within the Health QoLD. The remaining 71 results are categorized as QoLIs within each of the QoLDs. The final list of QoLDs and QoLIs identified in this study is presented in Figure 7.0.

Reporting Bias

All 80 studies met the inclusion criteria outlined in the methods section. As expected, the risk of bias emerged during the categorization stage. For example, the QoLI Family was cited in 27 of the identified studies. It could be argued that this validates Family as a QoLD rather than a QoLI. However, the researcher positions Family as a QoLI within the QoLD Relationships. Additionally, excluding outcomes deemed irrelevant to the general population presented a further risk of bias. Such risk was inherent in a study of this kind. As planned, the researcher categorized QoLI based on their best judgment before verifying with an academic supervisor.

Certainty of Evidence

The researcher suggests that the certainty in the body of evidence is high due to the study design and the explicit nature of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. While a risk of bias emerged during the data synthesis stage, the pre-proposition of QoLDs mitigated such risk, and validation by the academic supervisor provided further certainty of the results.

Study Limitations

While including 80 studies is comprehensive, a limitation is the reliance on PsycINFO as the sole database searched. Including multiple databases would have provided a more thorough overview of the QoL literature. Furthermore, although the study aimed to identify the conceptualization of QoL, studies focusing on individual QoLDs and QoLIs were not included, and potential outcomes may have been overlooked.

Other Information

This SLR was not registered and did not receive support, financial or otherwise, from a third party. The entire protocol is presented in the methods section. The researcher and academic supervisor declare that they have no competing interests in the study.

Discussion

The findings of this study support the needs previously identified across various domains of well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Donaldson et al., 2022; Franklin, 2019; Judith, 2004; Maslow, 1943; Ryff, 1989; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002; Seligman, 2011), validating the eight QoLDs proposed earlier in this paper. Additionally, two sub-domains and 71 QoLIs have been identified (Figure 7.0), adding greater specificity to our understanding of each domain in both academic and practical contexts. The QoLDs and QoLIs identified within the SLR provide valuable insight for PPCs to enhance their coaching practice. However, the effective implementation of these findings and their translation into the coaching profession requires further consideration. Schalock and Verdugo (2002) emphasize the importance of measuring and evaluating QoLDs and QoLIs within the microsystem. The aims for the remainder of this paper are to:

-

Produce a model of well-being which conceptualizes QoL based on these findings.

-

Create a coaching tool that supports PPCs and clients in evaluating QoL.

The Flourishing Life Model

The Flourishing Life Model (FLM) (Figure 8.0) is presented as a contemporary conceptualization of well-being, which aims to encapsulate the QoLDs validated in the SLR and provide a definition of each for researchers and practitioners. Schalock et al. (2016) explain that the theory of QoL begins with a conceptual model that explains the hypothesis, integrates work in the field, and provides a basis for application. Such a model must organize knowledge, provide a common language, and include key components without specifying how they work (Anguera, 1997; Llewellyn & Hogan, 2000), ensuring a clearly defined concept and the incorporation of other accepted theories. The definitions provided for each QoLD have been crafted by synthesizing the relevant definitions from the previously cited models of well-being.

Health: is a state of physical and mental well-being that enables individuals to engage in daily life with vitality, resilience and emotional harmony. It encompasses the foundational elements of survival, ensuring the body’s physiological functions and energy levels support optimal performance, longevity and overall quality of life.

Wealth: encompasses an individual’s financial and material well-being, providing basic needs, economic stability and access to essential resources that create opportunities for social mobility and personal growth.

Positive Emotion: encompasses emotional and hedonic well-being, characterized by the experience of frequent and intense feelings of happiness, joy and contentment. It involves the capacity for emotional regulation, enabling individuals to cultivate optimism, gratitude and resilience.

Self-Esteem: pertains to intra-personal well-being, reflecting an individual’s sense of self-acceptance, self-worth, and self-respect. It involves recognizing and valuing one’s abilities and achievements, which contributes to a well-founded sense of self-confidence.

Positive Relationships: pertain to social well-being, extending beyond one’s relationship with self to encompass the quality, depth and meaningfulness of interpersonal relations. They provide support, companionship and a sense of belonging, while fostering an individual’s capacity for empathy, cooperation and mutual growth.

Autonomy: is the ability to make independent choices and act in alignment with one’s values and beliefs. It is facilitated by environmental well-being, ensuring that individuals have the freedom, resources and opportunities to make meaningful decisions and express themselves authentically.

Self-actualization: is underpinned by eudaemonic well-being, where an individual strives to realize their full potential, personal excellence, and meaningful goals. The process involves a dynamic interplay between personal development and achievement.

Self-Transcendence: is encapsulated by spiritual well-being, involving the expansion of one’s perspective beyond personal concerns to connect with something greater, such as a higher purpose, spiritual beliefs, or the broader community. It fosters a sense of meaning and purpose that transcends individual existence through contribution to the well-being of others.

Methodical and Dynamic Approaches to the FLM

Previous models of well-being have employed varying approaches in presenting proposed needs. The use of a pyramid has been incorporated across several models (Franklin, 2019; Schalock & Verdugo, 2002). Most famously, Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs is commonly presented as a linear path towards self-actualization, where one must fulfill their basic needs before higher psychological needs can be considered. However, this was not how Maslow himself presented his work, and recent attempts have been made to revolutionize the presentation of his theory (Kaufman, 2020).

Despite this, survival needs such as health are likely to be addressed before thriving needs, such as autonomy, or actualization needs, such as self-transcendence (Franklin, 2019; Maslow, 1943). This methodical approach may see a client focus on their health before progressing through the model in a clockwise direction towards self-transcendence. To display this progression, Franklin’s (2019) grouping of needs has been incorporated and expanded, using the terms “survive”, “thrive” and “actualize” to highlight the progressive nature of the eight QoLDs.

Conversely, the researcher highlights that engaging in a random act of kindness (Lyubomirsky & Sheldon, 2005), such as helping an elderly person cross the street, would be considered an act of self-transcendence. Engaging in such an act does not require the fulfillment of the other QoLDs. Whilst it may appear logical to enhance one’s QoL by beginning with health, clients may choose to focus on a QoLD that they feel drawn to when using the model, which their current life circumstances will likely determine. This dynamic approach enables clients to prioritize the aspect of life that they consider most important in the present moment and develop it further. The effective application of the FLM requires PPCs to adopt a client-centred approach, explaining the methodical and dynamic approaches, and facilitating the development of the chosen QoLD.

The Rubik’s Cube of Wellness

Marinelli and Plummer (1999) proposed six interactive and dynamic core domains, which they refer to as The Rubik’s Cube of Wellness. They explain that one dimension cannot be affected without influencing the others. Their research explores the impact of exercise on core domains beyond the physical, concluding that all other components are positively affected. Moreover, Schalock et al. (2016) present their model as a series of components, each represented by a cog, to denote and depict the interconnected nature of each component.

The FLM adopts the Rubik’s Cube of Wellness by presenting the eight QoLDs as a wheel with a geometric overlay. This aims to provide a visual representation of the countless ways in which a positive impact on one QoLD can influence another QoLD. For example, increasing one’s self-esteem may lead to heightened levels of self-expression, economic growth provides greater resources for self-actualization, and the cultivation of positive emotions will likely have a positive influence on relationships and vice versa.

The Wheel of Life

The WoL is a tool designed to evaluate QoL and has been positively received by scholars and practitioners for many years. The early critique of Byrne’s (2005) WoL can now be resolved, as the results of the SLR provide an academic underpinning to an updated version of the tool (Figure 9.0). This version of Byrne’s (2005) model incorporates the eight QoLDs verified by the SLR and has been designed to support PPCs in evaluating QoL, providing an evidence-based approach to the popular tool.

The proposed WoL follows a similar application approach to previous versions of the model, where clients assess their satisfaction levels across each QoLD by selecting a score from 1 to 10. By doing so, the model provides a clear and simple interpretation of results for PPCs and clients, supporting its successful application to coaching practice (Schalock et al., 2016). Clients record the level to which they are fulfilled across each domain on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree, 10 = completely agree), which is presented as the WoL. Each QoLD will receive a score between 1 and 10. Barcaccia et al. (2013) explain that the evaluation of QoL should be compared to the combined evaluation of each QoLD. To achieve this, interpretation of the results will follow the methods of the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2009), where the sum of scores across each QoLD is combined to determine an overall score for QoL. As the WoL includes 8 QoLDs, scores will range from 8 (minimum) to 80 (maximum).

The Mental Health Continuum

Keyes (2002) first introduced the mental health continuum (Figure 10.0) by presenting mental health as a four-part scale ranging from mental disorder, languishing, moderate mental health, and flourishing. Since then, it has been widely adopted in the field of PP (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019). The validity of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form Questionnaire has demonstrated that interpreting the aggregate score of results is more informative than examining individual factors alone (Yeo & Suárez, 2022), supporting the suggested approach to measuring QoL.

Scores from the WoL can be translated onto the mental health continuum to determine the client’s QoL, allowing PPCs to offer a quick and simple overview of a client’s QoL. Four terms and definitions are offered as more appropriate alternatives for the context of QoL: flourishing, content, struggling, and crisis. Categorizations are based on the percentile of the results. For example, scores in the top 25th percentile are considered to be flourishing, those in the 25th-50th percentile are content, those in the 50th-75th percentile are struggling, and those in the bottom 25th percentile are in crisis.

While the measurement of QoL may provide the coach with insight into the level of flourishing across each QoL domain, the researcher warns that this score should be used for insight purposes only due to the limitations of self-report measures (Kormos & Gifford, 2014). Further research is required to test the validity of this tool.

Quality of Life Indicators

The SLR identified 71 QoLIs, which have been presented within the eight QoLDs to display the deconstruction of QoL (Cummins, 2005). However, the researcher suggests that the QoLIs listed in this paper are not exhaustive. For example, gratitude, forgiveness, self-acceptance, post-traumatic growth, and the use of character strengths are not mentioned in the QoL literature despite their known impact on well-being (Boniwell & Tunariu, 2019; Seligman et al., 2005; Wade et al., 2014). It is suggested that the number of QoLIs is significantly larger than those identified in this study, and that the list presented offers a foundation upon which to build. Future research should aim to build and refine this list, utilizing the existing literature on Positive Psychology while categorizing each QoLI within the QoLDs presented in the FLM.

Conclusion

Positive Psychology is the “science and profession which aims to understand and build upon the factors which enable individuals, communities, and societies to flourish” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). To achieve this goal, the field must develop a clear understanding of what flourishing entails and establish a well-defined conceptualization of the concept. Flourishing has been defined as “a state of positive mental health; to thrive, to prosper and to fare well in endeavors free of mental illness, filled with emotional vitality and function positively in private and social realms” (Michalec et al., 2009). However, to date, no previous models of well-being have provided a holistic conceptualization of what is required to flourish in life.

The QoL literature has demonstrated its difficulties in conceptualizing the phenomenon, and researchers have struggled to agree on a set of life domains that combine to encompass QoL (Kelley-Gillespie, 2009). Additionally, the most prominent theories of well-being have failed to produce a series of specific indicators that, if fulfilled, would lead to a flourishing life (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Franklin, 2019; Maslow, 1943; Ryff, 1989; Seligman, 2011).

Comparisons were drawn between several theories of well-being to determine a set of eight potential QoLDs: health, wealth, positive emotion, relationships, autonomy, self-actualization, and self-transcendence. However, further validation was sought through an exploration of the QoL literature.

This research paper aimed to:

-

Provide further validation of the eight QoLDs presented above

-

Identify the most prominent QoLIs within each

-

Produce a model of well-being which conceptualizes QoL based on these findings

-

Create a coaching tool that supports PPCs and clients in evaluating QoL

A SLR was conducted to validate these QoLDs and identify the most prominent QoLIs in the literature since Schalock and Verdugo (2002). A total of 181 records were screened, and 80 journal articles were included to produce 80 conceptualizations of QoL since Schalock and Verdugo’s (2002) study. The results of the SLR provided 132 individual validations for the eight QoLDs proposed by the researcher. A further 718 individual outcomes were identified and synthesized to produce two subdomains of health (physical and mental) and 71 QoLIs.

The FLM was presented as a new model of well-being that conceptualizes the findings of the SLR while integrating previous models. PPCs and clients may adopt a methodical or dynamic approach to applying the model, thereby facilitating a client-centred approach (Passmore, 2021). Its presentation as a wheel aims to highlight this non-hierarchical structure, while the geometric pattern symbolizes the interconnected nature of each QoLD through the Rubik’s Cube of Wellness (Marinelli & Plummer, 1999).

PPCs are responsible for creating the conditions that support the holistic development of their clients (Frisch, 2013). Developing skills and capabilities in just one domain can inhibit the client from actualizing their true potential (Hawkins & Turner, 2019). A client may choose to explore any of the QoLDs at any given time; however, focusing on a single domain is proposed to be the most effective approach. Narrowing the scope of attention enables deeper self-reflection, increased clarity, and more tangible progress. Research in goal-setting and behaviour change suggests that focusing on one meaningful area at a time enhances commitment, builds self-efficacy and reduces the mental strain associated with divided attention and task complexity (Locke & Latham, 2002).

The researcher also suggests that developing a Growth Mindset can be foundational for clients engaging in the coaching process, particularly when navigating the complexities of personal change. According to Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1983) Transtheoretical Model of Change, behaviour change is cyclical, involving stages such as contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance and often relapse. A Growth Mindset, as defined by Dweck (2006), is the belief that abilities can be developed through effort and perseverance, enabling clients to persist through setbacks and normalize relapse as part of the change journey. Rather than perceiving failure as a stopping point, clients with a Growth Mindset are more likely to interpret it as feedback, reinforcing their resilience and motivation. According to Dweck (2006), individuals with a Growth Mindset believe that their abilities can be developed through effort and learning, which increases their resilience in the face of setbacks and enhances their motivation to pursue long-term goals.

Clients may also benefit from the Best Possible Self Positive Psychology Intervention (King, 2001), which helps create a vision of their fulfilled potential within a given QoLD and the creation of meaningful goals. Once goals have been achieved within a specific QoLD, PPCs may support their clients in exploring additional domains, contributing to a well-rounded upward spiral of personal growth and well-being (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018). However, this process is not linear, and it does not imply that all domains must be addressed equally. The Wheel of Life encourages clients to identify the QoLDs most meaningful to them in the present moment and to define what success looks like in those areas.

Evaluating QoL is an essential task for PPCs aiming to enhance the well-being of their clients (Schalock et al., 2016). This paper provides an evidence-based take on Byrne’s (2005) WoL, which was designed to measure both QoL and each QoLD that resides within. The aim is to provide a simple, evidence-based tool for PPCs to evaluate their client’s QoL. A flourishing life is not contingent on achieving a perfect score of 10 in every domain, but is considered to be present when a client scores 60 or more out of 80, indicating a balanced and overall quality of life. Whilst the personal appraisal method has been widely employed in previous attempts to measure QoL and QoLDs (Cummins et al., 1994; Frisch, 2013; Priebe et al., 1999), the researcher was unable to identify empirical evidence for the reliability and validity of the WoL as a measurement tool. Future research should test the effectiveness of the proposed instrument.

The researcher’s hope for this paper is that the above conceptualization of QoL will support both the field of PP and PPCs in understanding how to fulfill their purpose. By facilitating the enhancement of an individual’s QoL (microsystem) through a strategy that leads to self-transcendence, PPCs can significantly influence the organizations (mesosystem) and societies (macrosystem) in which their clients reside (Schalock et al., 2016). Such an approach may lead to achieving the core goals of Positive psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

Author

Kris Domokos is a Positive Psychology Coach, researcher and entrepreneur with a deep commitment to helping others fulfil their potential and experience life from a state of well-being. He is the founder of Flourish, a Positive Psychology Coaching company based in the Cayman Islands, which develops evidence-based initiatives to enhance individual, community and societal flourishing.

Kris’s coaching philosophy was shaped during his early career in elite sports environments across Europe, the Middle East, and the Caribbean, and later refined as he applied his practice beyond sport and across all areas of life. His passion for personal growth as a pathway to community and global flourishing stems from a deep belief that each of us is present in this shared experience of life to contribute to the well-being of one another. He gives thanks to God for the opportunity to use his gifts in the service of others and the pursuit of our collective well-being.

_and_the_hierarchy_of_needs_(right).png)

_and_the_hierarchy_of_needs_(right).png)